Comparative law I. Legal regulation of the condominium or apartment ownership – the Hungarian and Swedish legal practice

Jenny Paulsson PhD, Tünde Mitták PhD

I. The law on condominiums in Hungary

The first law on condominiums was promulgated in 1924 that was changed by Act XI of 1977 which was enacted by Act CLVII of 1997. In order to resolve the high number of problems that occurred in practice, it became necessary to prepare a more current and precise law. This is Act CXXXIII of 2003 on Condominiums.

The condominium property represents a specific property in our law and order – a transition is constituted between business associations with legal personality and unincorporated business associations. The condominium property became institutionalized as a special form of the collective ownership, the condominium is quasi „incomplete legal entity”.

The codification of the Hungarian Civil Code (hereinafter: old Ptk.) happened in 1959 and the condominium property was defined in 1977 by the old Ptk. (Section 149 was established by Act IV of 1977, effective as of 1 March 1978). This meant if specified parts of the building – primarily the apartments – are owned separately by the co-owners, it is still possible to establish common ownership on a building (condominium property). The establishment of condominium property required the agreement of the co-owners incorporated into the charter document and the recording of condominium ownership into the real estate registry. At the request of any co-owner, a court may also mandate the transformation of the common property into condominium property. In this case the charter document shall be replaced by the court ruling. The rules applying to common property shall be applicable to condominium property,with the deviations specified in separate law.

Later the main rule in the old Ptk. was only this: The rules applying to common property shall be applicable to condominium property,with the deviations specified in separate law. This separate law was the Act CXXXIII of 2003 on Condominiums.

In the beginning this act defined a condominium property that is established when, in a building at least two stand-alone apartments or rooms not used as apartments, or at least one stand-alone apartment and one room not used as apartment specified in the charter document and technically divided, became the separate properties of the co-owners.

In accordance with Section 5:85 paragraph 1 of the currently effective Ptk. (hereinafter: new Ptk.) a condominium becomes in a building at least two stand-alone apartments or rooms not used as apartments, or at least one stand-alone apartment and one room not used as apartment specified in the charter document and technically divided became the separate properties of the co-owners, but the building sections, building fixtures, rooms not used as apartment and apartments not specified as separate property become the shared property of the co-owners. While according to Section 5:85 paragraph 5 of the new Ptk. rules applying to common property shall be applicable to condominium property, till then we can read in the Section 4/A of Act CXXXIII of 2003 on Condominiums (hereinafter: Act of Condominiums) that in connection with condominium property, the provisions of the Ptk. shall apply in respect of questions which are not regulated in this Act.

In accordance with Section 5 paragraph 2 of the Act of Condominiums a condominium may be established by the owners of individual units or the owner of the building as a sole founder laying down his decision to establish a condominium in the bylaws. However a condominium shall be deemed established when registered in the real estate register. The bodies of the association, their competencies and rights and obligations, and the rules for the assessment of maintenance fees shall be laid down in the organizational-operational regulations.

The obligatory content of the organizational-operational regulations are ordered by Section 13 paragraph 2, which are the below mentioned ones:

a) for the use and utilization of the private property of each owner of individual units, and the accounting and payment of utility and other service charges that cannot be measured separately for each individual unit;

b) for the upkeep of common elements, including:

– the assessment of the maintenance fee and for the collection of unpaid fees,

– the appropriation of the renovation reserve, if one exists;

c) for the house rules of the condominium building;

d) for the jurisdiction and procedure of the full or partial meeting of the association;

e) for the competence and duties of the managing agent or the head and members of the governing body;

f) for the powers and duties of the audit committee, or of the association if there is no audit committee.

The organizational-operational regulations are needed to adopt by the association in the inaugural meeting – or in a meeting held within sixty days of the inaugural meeting – by a simple majority of all owners of individual units. The association shall have powers to revise the organizational-operational regulations at any time. The organizational-operational regulations, and/or any amendments therein, shall be attached to the property registration documentation.

The condominium bodies are the following:

- the general meeting is the supreme decision-making body of the association of condominium owners,

- the affairs of the association shall be attended to by the managing agent or the governing body (shall comprise at least one chairperson and two members),

- in a condominium building containing more than twenty-five units an audit committee shall be elected to control the financial affairs of the association.

The economic control assistance (Section 51/A–51/B. of Act of Condominiums), the duty of registration concerning of the real estate management activities on a commercial scale and the obligation of training and licensure of the professional qualifications (Section 52–55. of Act of Condominiums) was established by paragraph (3) Section 308 of Act LVI of 2009 (in force: as of 1. 10. 2009.) An assistant for economic control functions shall be employed to support the audit committee, or the body exercising control if

- the financial turnover of a condominium association exceeds twenty million forints in a year, or

- the number of units – which are owned individually according to the bylaws – and non-residential units is more than fifty.

The assistant for economic control functions may be a person authorized to provide accounting services under the Accounting Act or a registered certified auditor. Any person who wishes to engage in condominium or real estate management activities on a commercial scale shall have the professional qualifications and other credentials prescribed in a decree adopted by authorization of this Act and shall meet the other requirements set out therein.

It seems that even these severer rules did not solve that problem of the condominium, that they were often found in mass near the insolvency caused by the wrong economic activity. There were more and more complaints and discontent against the managing agent, the number of lodging an appeal with the court to have the resolution annulled or to ask of the minority rights was increased. In this background the Act XI of 2014 was promulgated and established in the Act of Condominiums the new rules, that judicial oversight of the condominium association’s operations, condominium bodies and their operations shall be carried out by the notary. (Section 27/A. of Act of Condominiums)

The notary exercising oversight shall check to determine as to whether:

a) the condominium’s bylaws, organizational-operational regulations, and their amendments are in compliance with the law;

b) the condominium’s operation, general meeting resolution is in compliance with the law, the bylaws and the organizational-operational regulations; and

c) the condominium operates in conformity with general meeting resolutions. (Section 27/A. paragraph 2 of the Act of Condominiums)

If the notary finds that the operation does not comply with the above rules, he shall call upon the condominium to restore the legality of operations. If the condominium fails to restore the legality of operations within sixty days from the time of receipt of the notary’s request, the notary may bring action in court within thirty days following the said deadline for seeking a court order compelling the condominium to restore the legality of operations.

Upon the notary’s action the court may the following:

a) overturn the resolution the general meeting has adopted not in conformity with Paragraph b) of Subsection (2) and may order – if deemed necessary – that a new resolution be adopted,

b) convene the general meeting in order to restore legality of operation or may order the notary or the audit committee to do so, or

c) impose a fine between one hundred thousand and five million forints upon the managing agent or upon the head or members of the governing body, as corresponding to the severity of the infringement, if legality of the condominium’s operation cannot be restored as under Paragraph a) or b) on account of the managing agent’s or the governing body’s unlawful conduct. (Section 27/A. paragraph 5 of the Act of Condominiums)

II. Apartment ownership in Sweden

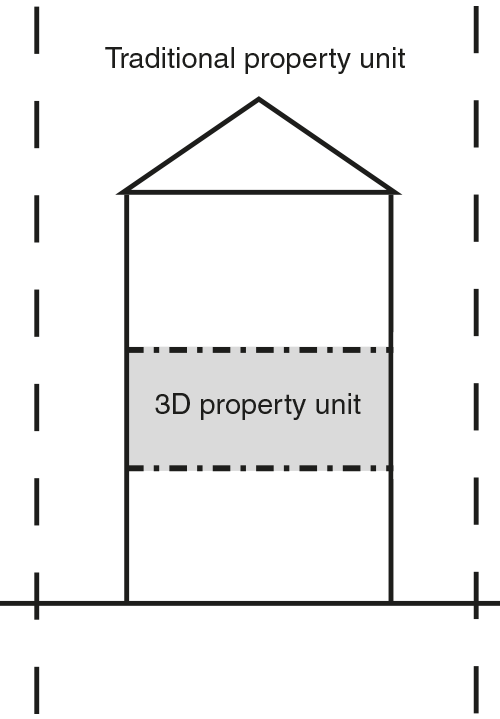

Apartment ownership in Sweden is considered as a form of 3D property ownership, as opposed to the traditional “2D” property unit. The traditional 2D property unit does not consist solely of the land surface, but includes a three-dimensional volume. In theory, it extends downwards to the center of the earth and upwards infinitely into the sky, but in practice only as much as can be used by the property owner. What separates the 3D property unit from the 2D property unit is the three-dimensional delimitation of it, i.e. that it is legally delimited both horizontally and vertically.

1. Example of the Swedish 3D Property Unit[2]

There exist different types of 3D property rights. The independent 3D property type is a volume of space that is subdivided and separated from the rest of the (2D) property. Often it is a larger unit, which can include several apartments or offices, or it can be used for facilities and infrastructure objects, such as tunnels. The condominium is an ownership right to a part of a building, usually with a share in the common property surrounding these individual parts and membership in an owners’ association.

There are also indirect forms of 3D property rights, including the tenant-ownership type, where a tenant-owner association owns the apartment building and the land on which it stands and the members will provide capital for the right to use the apartment.

2. Types of 3D Property Rights[3]

| Independent 3D property | Air-space parcel |

| 3D Construction property | |

| Condominium | Condominium ownership |

| Condominium user right | |

| Condominium leasehold | |

| Indirect ownership | Tenant-ownership |

| Limited company | |

| Housing cooperative | |

| Granted rights | Leasehold |

| Servitude | |

| Other rights |

Legislation regulating condominiums (ägarlägenheter) was introduced in 2009 in Sweden. It was not enacted as a separate law, but relevant sections were added to the Land Code and the Real Property Formation Act. The condominium is regarded as a special form of three-dimensional (3D) property, and legislation on 3D properties (3D-fastigheter) was introduced in 2004. It is thus a rather new phenomenon in Sweden.

Sweden has since the 1930’s also an indirect form of apartment ownership, the tenant-ownership (bostadsrätt), which has similarities with the condominium. This is the more common way in Sweden to obtain individual rights to a specific apartment. There are many similarities between tenant-ownership and condominium ownership, but an important difference is that instead of owning a physical part of the building the ownership is represented by a share in the capital of the economic association that owns the property. The purpose of the association is to convey tenant-ownership rights to apartments in the building that is owned by the association. To the ownership of that share is connected the right to use a specified apartment in the property owned by the association, a right which is not limited in time. The management of the tenant-ownership building is handled in a co-operative manner, where the association manages the building whereas the tenant-owner has the responsibility of maintaining the interior of the apartment.

A 3D property is defined in the Swedish legislation as a property unit which in its entirety is delimited both horizontally and vertically (Swedish Land Code, Chap. 3, s. 1a). Condominium (ownership apartment) is defined as a three-dimensional property unit intended to contain nothing but one single residential apartment (Swedish Land Code, Chap. 3, s. 1a).

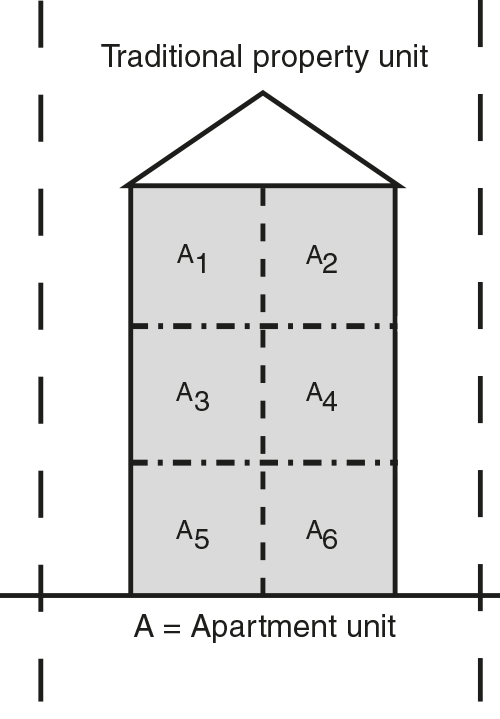

3. Example of the Swedish Condominium[4]

The Swedish condominium belongs to the dualistic condominium ownership type, which means that each resident owns the physical part of the building where his/her apartment is located and in addition has a share in the common property of the building and land.

In general, the same rules that exist for traditional 2D properties also regulate 3D properties. However, some special rules have been added, e.g. that a 3D property unit may be formed only if the facility containing it already has been constructed and that it has to be provided with the additional rights that it will need in order to be used for its purpose. There are some specific rules added also for the condominium. It can only be formed for residential purposes and only in new buildings, or a building that has not been used for accommodation during the eight years before the condominium was formed. The reason for this rule is to avoid that the existing residential apartments are transformed into ownership apartments. There must be at least three ownership apartments closely connected to each other in order to facilitate the management of the apartment building. The purpose of this rule is to avoid that the property division becomes too complex, to enhance the opportunities for a good living environment and to promote the cooperation between adjoining apartments. It is important to provide for necessary rights when the condominium is formed, such as access to the apartment and availability of different facilities.

The condominium is formed through one of the regular property formation measures, i.e. subdivision, partition, amalgamation or re-allotment. The cadastral authority will evaluate whether all necessary conditions in the legislation are fulfilled, both when it comes to general suitability of the property and the above-mentioned special requirements. It will be recorded in the real property register. Boundaries, rights and obligations are determined in the property formation.

Common ownership and management

The Swedish legislation does not contain detailed regulation on e.g. where the boundaries between property units are to be located.

The main rule is that an apartment unit within the condominium building consists of the actual space of the apartment and the surface of the structures that are separating the apartments. It is not specified in the legislation what parts of the building that should be in private or common ownership, but this is decided for each condominium in the cadastral procedure. Common property is the structural building parts, stairs, pipes, etc., but it can also be possible to use easements where the condominium owners have the right to use parts of another property unit containing the necessary facilities.

There is no compulsory form of cooperation between the apartment units provided in the legislation, but normally a joint facility and/or a joint property unit is formed and is required if joint facilities or joint property units are formed, which is nearly always the case and means that in most cases this will be the standard solution. The joint property unit will include common property and facilities. Usually, one joint facility is formed for each condominium building, but if needed there can be several joint facilities within one building, or one joint facility where there are differentiated shares for separate parts of the condominium building.

The joint facility can be managed by an association formed by the owners, or by part-owner management. Part-owner management means that all owners of the facility have to agree on all activities and is mainly used when few owners are involved. Association management is the most common type, especially when larger joint facilities are involved. The owners’ association constitutes a legal person, with the management activities defined by statutory provision, articles of association and decisions by meetings. The operational costs are paid by each property owner.

The owners’ association should e.g. create clear rules for management and take action against disturbances amongst the residents. It is also possible for the association to issue house rules for the use of the common property.

The general rules for rights between neighbours are applicable also to 3D properties, but in addition there are some special rules concerning access to the adjacent property for repairs, construction work, etc. The law also provides protection from insufficient maintenance or damage from the adjacent property. If occupants of the apartments units cause disturbances to an extent that cannot be tolerated, the owner can be ordered under penalty that the disturbance should stop.

Problems with condominiums

During the first years after the introduction of the condominium legislation, it has been working well. However, the interest has not been as great as the legislators expected. Some reasons have been hesitation about this new type of property and issues related to management, co-ordination, etc. One limiting rule is that a 3D property unit may only be formed if it is considered more suitable than other measures and that it must lead to better management or facilitate financing or construction. Another reason is that condominium can only be constructed in buildings not used for housing, although a governmental inquiry has recently presented a proposal to make it possible to convert rental apartments into condominium. Since the legislation is not that detailed in its regulations, some specific questions regarding e.g. insurance solutions and mortgage had to be solved by the industry, but this was not done until after the introduction of condominium legislation. Another contributing factor is the already existing and well-established form of tenant-ownership. There is not enough knowledge about the benefits of the condominium compared with tenant-ownership, and thus there is a lack of demand.

Differences between condominium and tenant-ownership

There are many similarities between the condominium form and the tenant-ownership form and the general public often has difficulties in understanding that there is any real difference between them. However, there are many differences with consequences of different types. As indicated above, the main difference is that the condominium apartment forms a separate 3D property unit with its own cadastral number in the real property register. It is owned directly and will have a registered ownership, while the tenant-ownership apartment is owned indirectly and is only a form of user right to the apartment. There are more possibilities for the owner to freely dispose of the apartment when it comes to transferring the apartment (where the tenant-owner has to be accepted as a member of the association) and to letting the apartment to anyone else (where the tenant-owner needs a permission from the association). This means that the condominium can be bought as an investment without the owner living there. The condominium owner can never be forced to leave the apartment if e.g. the owner causes disturbance for the neighbours to a level that cannot be tolerated, but the tenant-owner can in the same situation lose the user right to the apartment.

The condominium owner has more control of the economy through a separate loan, instead of paying to the association for instalments and rent as the tenant-owner does. This also means that the individial costs will be higher for the condominium owner for registration, insurance, property tax, etc., but the joint costs will be smaller, as opposed to for the tenant-owner. There is greater possibilities for the condominium owner to have influence on the running costs for e.g. water and sewage and electricity through separate agreements, while the tenant-owner pays this through the assocication fee. In all, the initial costs for purchasing the apartment will be higher for the condominium, but the monthly living costs will be lower.

III. Summary

In Hungary, the first law on condominiums was promulgated in 1924 which was a separate law. Legislation was changed a lot and now the effective law is Act CXXXIII of 2003 on Condominiums. This Act entered into force on 1 January 2004. The condominium property represents a specific property in our law and order – a transition is constituted between business associations with legal personality and unincorporated business associations.

Condominium is defined in the new Ptk. as that becomes in a building at least two stand-alone apartments or rooms not used as apartments, or at least one stand-alone apartment and one room not used as apartment specified in the charter document and technically divided became the separate properties of the co-owners, but the building sections, building fixtures, rooms not used as apartment and apartments not specified as separate property become the shared property of the co-owners [Section 5:85 paragraph 1].

A condominium may be established by the owners of individual units or the owner of the building as a sole founder laying down his decision to establish a condominium in the bylaws but it shall be deemed established when registered in the real estate register.

In Sweden, the legislation regulating condominiums was introduced in 2009 and so it is a rather new phenomenon. It was not enacted as a separate law, but relevant sections were added to the Land Code and the Real Property Formation Act. The condominium is regarded as a special form of three-dimensional (3D) property. A 3D property is defined in the Swedish legislation as a property unit which in its entirety is delimited both horizontally and vertically (Swedish Land Code, Chap. 3, s. 1a). Condominium (ownership apartment) is defined as a three-dimensional property unit intended to contain nothing but one single residential apartment (Swedish Land Code, Chap. 3, s. 1a).

The Swedish condominium belongs to the dualistic condominium ownership type, which means that each resident owns the physical part of the building where his/her apartment is located and in addition has a share in the common property of the building and land. In Sweden the condominium can only be formed for residential purposes and only in new buildings, or a building that has not been used for accommodation during the eight years before the condominium was formed. There must be at least three ownership apartments closely connected to each other in order to facilitate the management of the apartment building and it need also be recorded in the real property register.

The condominium bodies are in Hungary:

- the general meeting is the supreme decision-making body of the association of condominium owners,

- the affairs of the association shall be attended to by the managing agent or the governing body (shall comprise at least one chairperson and two members),

- in a condominium building containing more than twenty-five units an audit committee shall be elected to control the financial affairs of the association.

The bodies of the association, their competencies and rights and obligations, and the rules for the assessment of maintenance fees shall be laid down in the organizational-operational regulations.

In Sweden, the joint facility can be managed by an association formed by the owners, or by part-owner management. Part-owner management means that all owners of the facility have to agree on all activities and is mainly used when few owners are involved. Association management is the most common type, especially when larger joint facilities are involved. The owners’ association constitutes a legal person, with the management activities defined by

- statutory provision,

- articles of association and

- decisions by meetings.

The operational costs are paid by each property owner. The owners’ association should e.g. create clear rules for management and take action against disturbances amongst the residents. It is possible for the association to issue house rules for the use of the common property as that as in Hungary too.

During the first years after the introduction of the condominium legislation, it has been working well. However, the interest has not been as great as the legislators expected that is have more reasons. For example there is a well-established form of tenant-ownership in Sweden which is a rather special system and there is not any similar type of it in Hungary.

Sweden has since the 1930’s also an indirect form of apartment ownership, the tenant-ownership (bostadsrätt), which has similarities with the condominium. This is the more common way in Sweden to obtain individual rights to a specific apartment. There are many similarities between tenant-ownership and condominium ownership, but an important difference is that instead of owning a physical part of the building the ownership is represented by a share in the capital of the economic association that owns the property. The purpose of the association is to convey tenant-ownership rights to apartments in the building that is owned by the association. To the ownership of that share is connected the right to use a specified apartment in the property owned by the association, a right which is not limited in time. The management of the tenant-ownership building is handled in a co-operative manner, where the association manages the building whereas the tenant-owner has the responsibility of maintaining the interior of the apartment.

As indicated above, the main difference is that the condominium apartment forms a separate 3D property unit with its own cadastral number in the real property register. It is owned directly and will have a registered ownership, while the tenant-ownership apartment is owned indirectly and is only a form of user right to the apartment.

There are more possibilities for the owner to freely dispose of the apartment when it comes to transferring the apartment (where the tenant-owner has to be accepted as a member of the association) and to letting the apartment to anyone else (where the tenant-owner needs a permission from the association). This means that the condominium can be bought as an investment without the owner living there. The condominium owner can never be forced to leave the apartment if e.g. the owner causes disturbance for the neighbours to a level that cannot be tolerated, but the tenant-owner can in the same situation lose the user right to the apartment.

The condominium owner has more control of the economy through a separate loan, instead of paying to the association for instalments and rent as the tenant-owner does. This also means that the individial costs will be higher for the condominium owner for registration, insurance, property tax, etc., but the joint costs will be smaller, as opposed to the tenant-owner. There are greater possibilities for the condominium owner to have influence on the running costs for e.g. water and sewage and electricity through separate agreements, while the tenant-owner pays this through the assocication fee. In all, the initial costs for purchasing the apartment will be higher for the condominium, but the monthly living costs will be lower.

We can say there is not enough knowledge about the benefits of the condominium compared with tenant-ownership in Sweden, and thus there is a lack of demand. In Hungary, we have not knowledge and experience about the tenant-ownership because it is an unknown system for us. In Hungary, we often think that the main problem of the area of condominium is the judicial oversight, whereas other cultures already have a well-established form of tenant-ownership which has been working well. It is a possibility of using another system that would make the Hungarian legal system on condominiums better.

Jenny Paulsson PhD

Associate Professor (docent) in Real Estate Planning and Land Law,

KTH – Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm

Tünde Mitták PhD

Lawyer, student

SFEJ – Intensiv Swedish for Academics, Stockholm

Kategória

Könyvajánló

A Magyarország helyi önkormányzatairól szóló törvény magyarázata

Negyedik, hatályosított kiadás

(2023. őszi kiadás)

Ára: 12000 Ft